In this blog and elsewhere, you have probably already seen the expression “Copernican revolution”. This expression highlights the fact that Nicolaus Copernicus (1473 – 1543) provoked a major change in perspectives by showing that it is more relevant to consider this is the Earth that is rotating around the Sun rather than the opposite. To this first upheaval echoes Galileo Galilei’s (1564 – 1642) works. The latter, on the basis of Copernicus’ work, among others, has definitively shown that Claudius Ptolemy’s (around 90 AD – about 168) system, published in the Almagest1Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖος, around 150 AD. Μαθηματική σύνταξις. An English translation: Gerald J. Toomer, 1998. Ptolemy’s Almagest, second edition, Princeton University Press, New York, United States of America. Available on-line. and according to which, in agreement with Aristotelian physics, the Earth was motionless in the centre of the World, was wrong.

I have already presented this, with a view from here. As I have indicated before, they were both preceded by Nicole Oresme’s (about 1320 or 1322 – 1382) work. Galileo also used Johannes Kepler’s (1571 – 1630) work, among others. Therefore, I have intentionally used the expression “Copernican revolution,” as well as “epistemic revolution.” But still remains the question I would like to tackle in this article: though this expression is commonly used, is it really relevant to talk about revolution? My purpose is also to lead you, my dear reader, to make some critical analysis of what I am publishing here.

What does “revolution” really name?

First of all, what do we mean when using the word “revolution?” According to etymology, it has been introduced into English to name the movement of an object in a circular or elliptical course around another or about an axis or centre.

At this point, you may be wondering if I do not give in to the pleasure of throwing a troll. Well, maybe, a bit ...

The point of view of the Enlightenment

Nowadays, the word “revolution” commonly refers to a dramatic and wide-reaching change in conditions, attitudes, or operations. The first occurrence of this usage concerning a scientific subject I have found comes from the Encyclopédie2Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert (editors), 1751-1772. Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Briasson, David, Le Breton and Durand, Paris, 35 volumes. Text in French. Available on-line. An English translation of some of its articles is available on-line.. It presents works from Isaac Newton3Especially his most famous one: Isaac Newton, 1687. Philosophiæ naturalis principia mathematica, John Streater, London. Text in Latin. Available on-line. An English translation: Ierome Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman, 1999. Isaac Newton: The Principia, Mathematical principles of natural philosophy, University of California Press. Available on-line. (1642 or 1643 – 1727) and some others as revolutions, that is to say as initiating some new era. Moreover, it seems that these so-called revolutions are an important reason in the initiation of the project of the Encyclopédie. In this book, “revolution” ultimately designates all that is part of the transformation of physical sciences, particularly mechanistic ones, between the 17th and 18th century. In short, it names the changes in scientific approach of which I have already presented some parts here.

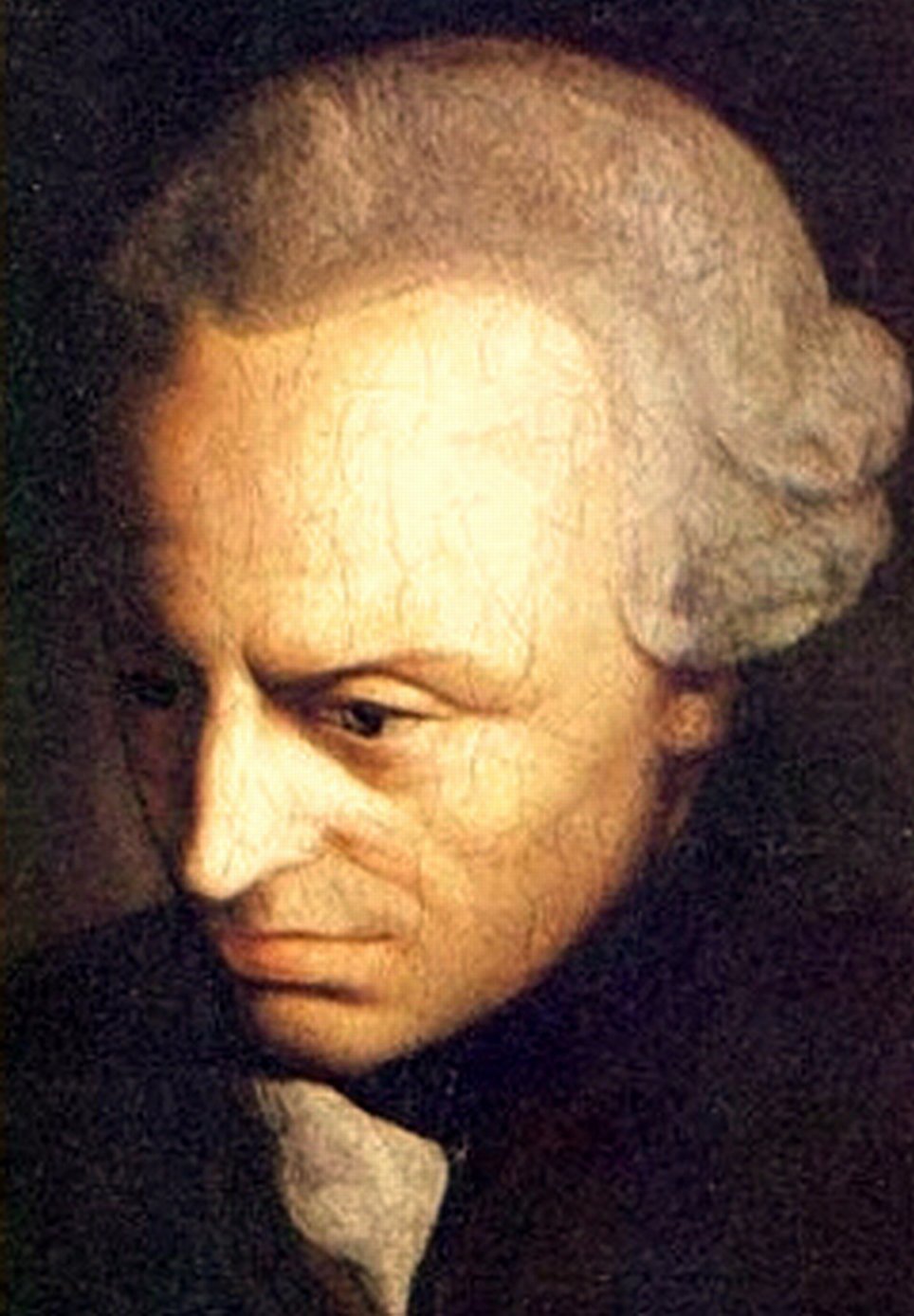

Concerning philosophy, Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) named “Copernican revolution” the transition from a geocentric system to a heliocentric one4Immanuel Kant, 1781. Critik der reinen Vernunft, Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, Riga, Holy Roman Empire. Text in German. Available on-line. An English translation from Paul Guyer and Allen Wood: Immanuel Kant, 1999. Critique of Pure Reason, Cambridge University Press. Available on-line..

A long story

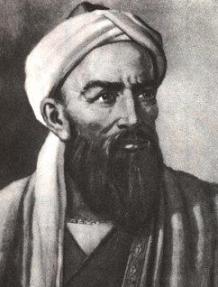

Using the word “revolution” supports the idea that some sudden change have been made. However, as I have already indicated elsewhere, back to antiquity there already were some models in which the Earth is not at the centre of the Universe. For instance, as reported Archimedes5Áρχιμήδης, Ψαµµίτης. Text in ancient Greek. Available on-line. An English translation by Thomas L. Heath: Archimedes, 1897. The Sand-reckoner, Cambridge University Press. Available on-line. (circa 287 – 212 BC), Aristarchus of Samos (circa 310 – 230 BC) already proposed such a model, as well as Seleucus of Seleucia6See for instance: Bertrand Russel, 1945. A History of Western Philosophy, Georg Allen & Unwin Ltd. (born around 190, active around 150 BC). Also, there are texts from ancient India mentioning such a system. Al-Bīrūnī (973 AD – 1048 or around 1052) has reported and commented these texts7See for instance: Abu al-Rayhan Muammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni, edited by Eduard Sachau, 1910. Al-Biruni’s India: an Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of Indiae, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., London..

Even by focusing only on the reintroduction of the heliocentric system during the early modern period, it clearly appears to be the results of some maturation. Indeed, as I wrote before, Nicole Oresme had already presented this system as credible8Nicole Oresme, 1377. Livre du Ciel et du Monde. Text in ancient French. Available on-line.. Before him, Ibn al-Shātir (1301 – 1375) had proposed a heliocentric system9See for instance: Victor Robert and Edward S. Kennedy, 1959. “The planetary Theory of Ibn al-Shātir,” in: Isis 50, pp. 227 – 235. Available on-line.. Then, Copernicus shows the interest of such a system10Nicolaus Copernicus, 1543. De revolutionibus orbium cœlestium, Johann Petreium, Nuremberg, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. Available on-line. An English translation by Edward Rosen: Nicolaus Copernicus, 1992. On the Revolutions, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America. Available on-line..

The Copernicus case

It will be useful for what comes later to note that Andreas Osiander (1498 – 1552), a theologian in charge of supervising the printing of Copernicus’ work, took the decision of his own to precede this work with a warning. This warning indicated that the heliocentric system is nothing but a calculation hypothesis11See for instance: John Henry, 2012. A Short history of scientific thought, Palgarve Macmillan, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom.. On the contrary, as soon as on the preface, Copernicus affirmed that this system is in conformity with the true constitution of the World. However, Robert Bellarmine (1542 – 1621) will rely on this warning to consider that Copernicus did actually consider the heliocentric system as nothing but a calculation hypothesis.

It is worthwhile to dwell a little on the case of Copernicus. Indeed, among all those I cite in this article, he probably is the one who worked the most individually. He was even relatively isolated. Anyway, he still had contacts with other astronomers, at least for example when he let circulating the manuscript often called Commentariolus12Nicolaus Copernicus, between 1511 and 1513. De Hypothesibus Motuum Cœlestium Commentariolus. Text in Latin. An English translation can be found in: Edward Rosen, 2004. Three Copernican Treatises, second edition, revised edition, Dover Publications, New York. Available on-line., which already presented a heliocentric system. There was no mention of the name of the author–Copernicus name, indeed. Nevertheless, it contributed to establish his reputation as an astronomer. It is this reputation that lead Georg Joachim von Lauchen, also known as Rheticus (1514 – 1574), to collaborate with Copernicus13Georg Joachim von Lauchen, 1540. Narratio prima, Franz Rhode, Dantzig, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. An English translation can be found in Rosen (2004), see note 12.. Therefore, the latter does not really correspond to the image of the scientist working alone and unrelated to the outside world.

Also, it is difficult to know how much Copernicus was exposed to the heliocentric theories elaborated before his. However, note that Domenico Maria Novara (1454 – 1504) hosted him during his studies in Bologna between 1496 and 1503. Domenico Maria Novara was already questioning Ptolemy’s authority, especially because of the complexity of his system14For Copernicus’ biography, one can refer to: Pierre Gassendi and Olivier Thill, 2002. The Life of Corpernicus 1473 – 1543, Xulon Press.. On the one hand, though he learned ancient Greek, Copernicus did not know Arabic. On the other hand, he studied in a university with many books, at a time of translation of Arab works. For example, until Rheticus brought him an edition of the original Greek text, he used a Latin translation by Gerard of Cremona (1114 – 1187) of the Arabic version of the Almagest.

Copernicus’ posterity

What helped in initial spreading of the Copernican system is the publication in 1551 of the Prutenic Tables by Erasmus Reinhold15Erasmo Reinholdo, 1551. Prutenicæ Tabulæ Cœlestium Motuum, Ulrich Morhard, Tübingen, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. Available on-line. (1511 – 1553), an ephemeris useful to calculate the apparent positions of the Sun, the Moon, and the planets. These tables are the first produced using the Copernican system and were of a higher precision than the previous ones. If we must recognise that their precision was first due to the quality of the observations of Reinhold, they will ensure a good dissemination to the system on which they are based.

Later, Kepler compiled works from several other authors, to which he added his own mathematical developments16Johannes Kepler, Nicolaus Copernicus, Michael Mästlin, and Johannes Shöner, 1596. Mysterium cosmographicum, Georgius Gruppenbachius, Tübingen, Holy Roman Empire. Reissued in 1621 with comments from Kepler. Text in Latin. Available on-line.. Eventually, Galileo has used works from Copernicus and Kepler and completed them with his own observations17Galileus Galileus, 1610. Sidereus nuncius, Thomam Baglionum, Venice. Text in Latin. Available on-line. An English translation: Albert Van Helden, 1989. Galileo Galilei, Siderius Nuncius, or The Sideral Messanger, The University of Chicago press. Available on-line..

I have cited many authors and books in the last paragraphs, even by comparison with what I usually do in this blog. This illustrate a fact I want to expose to your sagacity: in fact of a revolution, one sees it is a rather long history.

The idea of a “Copernican revolution” is actually introduced by authors belonging to the Enlightenment and it has been made with a purpose: for these authors, medieval thought was hampered by the domination of the Aristotelian system and scholasticism. Inasmuch as Aristotle’s (384 – 322 BC) physics proved to be entirely wrong and as when you read some scholastic texts you are struck by the clumsiness of the reasoning, we can certainly praise having getting rid of these approaches. However, as these authors had such an agenda, they have presented things in a rather biased, if not partial, way.

A flourishing thinking

In fact, the Middle Ages, still more than a thousand years, is actually a more flourishing period than too often portrayed. Let’s take an example which seems to me quite representative.

Few years ago, Ivano Dal Prete (born in 1971) found a book from Fausto da Longiano published in 154218Ivano Dal Prete, 2014. “Being the World Eternal: The Age of the Earth in Renaissance Italy”, in: Isis volume 105, number 2, pp. 292 – 317.. This book tackles with meteorological science19Fausto da Longiano, 1542. Meteorologia, Venice. Text in old Italian.. At these times, it covered a wider scope than nowadays, including for instance geology and oceanography. Though scholars of the times used Latin to communicate to their peers, this book is written in (old) Italian: this is some popularisation work.

Indeed, the printing press was then in full expansion, as a century before Johannes Gutenberg (circa 1400 – 1468) introduced in Europe removable type printing20It seems to me that the seminal work concerning the importance of printing on the evolution of thought is: Elizabeth Eisenstein, 1979. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications and cultural transformations in early-modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, New York. The author has made a version dedicated to popularisation: Elizabeth Eisenstein, 1983. The Printing revolution in early modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.. Their prices having fallen considerably, a new public for the books had been constituted. As a consequence, books of all types appeared, not just for scholars. Among these works, many aimed to popularise the knowledge of the time.

The age of the Earth

So here we have a book that can potentially be read by anyone–well, anyone who can read. Its purpose is to present what is commonly accepted, rather than to address potentially controversial topics. Still, as already indicated, what we now call geology was part of the subject the author intended to develop. As a consequence, he addresses the question of the age of the Earth in his book.

In the Encyclopédie, articles concerning fossils and the Deluge describe the years preceding its publication to be dominated by history of Creation as reported in Genesis. Biblical literalism, i.e. literal interpretation of all that is written in the Bible, was supposed to be the norm. Then, according to this literalism, the World would have been created around 4000 BC, precisely October 22nd, 4004 BC according to James Ussher’s (1581 – 1656) calculations21James Ussher, 1650. The Annals of the World, E. Tyler, London. Available on-line..

If, as stated by encyclopedists, at this time Western thought was dominated by biblical literalism, Fausto da Longiano should indicate that the World was no more than 6000 years old. However, this is not the case: his book present a conception, indeed an Aristotelian one, according to which the slow erosion due to running waters and the accumulation of debris at the bottom of the ocean causes the renewal of the ocean floor. Then, the floor moves cyclically on the surface of the Earth, leaving behind new emerged areas and new mountains. A phenomenon presented as too slow to be humanly perceptible. It is even indicated that the soil is completely renewed every 36,000 years and that this duration is not a problem, the World being presented as eternal.

By the way, if you are wondering, the age of the Earth is nowadays strongly estimated at about 4.55 billion years22See for instance: US Geological Survey, 1997. Age of the Earth. Available on-line..

But what the Church is doing?

There is another point worth to be noted: in his work, Fausto da Longiano does not mention Genesis in any way. However, nothing indicates that the author considered his text could have offended or even surprised his readers. Likewise, Ivano Dal Prete has found no evidence that the Church had grieved him. Everything indicates that the book simply presents knowledges fairly widespread at the time.

In the purpose to avoid overflowing my point, I will not present the whole of Ivano Dal Prete’s article. To summarise, he looked for other scientific books of the time, both in vernacular and Latin, dedicated for some popularisation as well as addressed to scholars. He found several books indicating the antiquity of the Earth, some emanating from seniors in the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. This idea is presented as valid at least since the beginning of the 13th century, when Aristotle’s teaching is gaining European universities.

However, you can easily understand that the authors of the Enlightenment considered the biblical vision of a young world being dominant, as Nicholas Eymerich’s (circa 1320 – 1399) Directorium Inquisitorum classifies the eternity of the world as a heresy23Nicolau Aymerich, 1376. Directorium Inquisitorium. Text in Latin. This book has been completed (its size did more than doubled) by Francisco Peña in 1578.. Thus, despite it appears that this last idea was quite widespread, there were clearly strong and even violent oppositions against it. We will see below other examples of this kind of opposition, but first it is necessary to clarify what was the position of the Church.

Can the Bible be questioned?

It is certain that the Church disapproves the idea that the World was not created by God. As we just seen it, at the end of Middle Ages, it appeared to condemn the idea that World may be eternal. Beyond this, it was not really interested in the exact way things have happened.

What does the Bible say about science?

In any case, the Bible does not say much about subjects of science (understood in its present meaning), save for History. On the latter subject, the Church did not allow anyone to question the biblical story. However, concerning the movement of the Earth in the Solar System, one can find some passages addressing the subject. They are in the Old Testament, starting with Joshua 10:12-13. By the way, in this article I use the translation from King James Version:

‘Then spake Joshua to the Lord in the day when the Lord delivered up the Amorites before the children of Israel, and he said in the sight of Israel, Sun, stand thou still upon Gibeon; and thou, Moon, in the valley of Ajalon. And the Sun stood still, and the Moon stayed, until the people had avenged themselves upon their enemies. Is not this written in the book of Jasher? So the Sun stood still in the midst of heaven, and hasted not to go down about a whole day.’

Undeniably, this passage claims that the apparent movements of the Sun and the Moon have been suspended. Anyway, in the end it does not imply that it is the Sun that revolves around the Earth or vice versa, as it only mentions observations that could have been done from the Earth.

Some other elements, depending on the adopted translation, may be interpreted as tackling the position of the Earth relatively to others stars. Thus, 1 Chronicles 16:30 indicates: ‘[…] the world also shall be stable, that it be not moved.’ Also, Psalm 93:1 states: ‘[…] the world also is stablished, that it cannot be moved.’ Likewise, Psalm 96:10 declares: ‘[…] the world also shall be established that it shall not be moved […]’ Next, Psalm 104:5 says: ‘Who laid the foundations of the earth, that it should not be removed for ever.’ Finally, Ecclesiastes 1:5 enunciates: ‘The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose.’

In the end, let’s face that these formulations are vague, sometimes even nothing but banalities. Though some stability in the ordering of the Universe is enunciated, none of these elements necessarily imply that the Earth has to stand still at its centre. Not even does it imply that there is actually a centre in the Universe.

An impossible literalism

This was Galileo’s point of view: for him, if God really had meant to tell the organisation of the World, then the Bible would not give so little allusive elements on the subject24Galileo’s letters exposing this point of view have been published and translated into English for instance in: Maurice A. Finnochiaro, 1989. The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History, University of California Press, Berkley. Available on-line.. Said with more modern terms, religion and science does not have the same ontological status, especially since, as I have already indicated, there is no positive definition of “God.” Therefore, religion cannot be used to determine the validity of a scientific fact. It also means that Biblical literalism does not hold.

Moreover, the impossibility of Biblical literalism was theologically established since a long time. Especially because of the question of parousia. Indeed, the biblical account indicates that Jesus will return to Earth–this is the second coming, called parousia. The moment of the parousia is indicated in Matthew 24:34, Mark 13:30 and Luke 21:32, these gospels having to report Jesus words:

‘Verily I say unto you, This generation shall not pass, till all these things be fulfilled.’

This indication is not really precise, the reason being the exact date would be known only from God (Matthew 24:36). Still, it is indicated that parousia was to occur in the generation that follows the sermons of Jesus. This was already a problem at the time of writing of the gospels, which were probably composed between 70 AD and 90, more or less ten years–that is to say, about a generation after the events25See for instance: Raymond Edward Brown, 1997. An Introduction to the New Testament, Doubleday, New York City.. Thus, the second epistle of Peter, probably written at the beginning of the second century, indicates that parousia has already taken place but that the sceptics do not know how to see the signs (2 Peter 3:1-13).

Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430) looked into this problem26Aurelius Augustinus, 413-426. De Civitate Dei contra paganos. Available on-line. An English translation by William Babcock: Augustine of Hippo, 2012. The City of God, New City Press, New York. Available on-line.. He noted that 2 Peter 3:8 says:

‘[…] one day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day.’

This lead him to the following reasoning (The City of God, Book 20, chapter 7):

‘Now the thousand years may be understood in two ways, so far as occurs to me: either because these things happen in the sixth thousand of years or sixth millennium (the latter part of which is now passing) […] so that, speaking of a part under the name of the whole, he calls the last part of the millennium–the part, that is, which had yet to expire before the end of the world–a thousand years; or he used the thousand years as an equivalent for the whole duration of this world, employing the number of perfection to mark the fullness of time.’

Then:

‘Besides, if a hundred is sometimes used for totality, as when the Lord said by way of promise to him that left all and followed Him “He shall receive in this world an hundredfold27Matthew 19:29, Mark 10:30.;” […] with how much greater reason is a thousand put for totality since it is the cube, while the other is only the square? And for the same reason we cannot better interpret the words of the psalm, “He hath been mindful of His covenant for ever, the word which He commanded to a thousand generations28Psalm 105:8.,” than by understanding it to mean “to all generations.”’

To sum it up in a more modern way, Augustine deduced that God is out of time and therefore we cannot consider the temporal indications to be absolute. As a result, the text cannot be read literally. It was thus clearly established by the middle of the fifth century that the Bible could not be interpreted literally.

Of course, during the Middle Ages thinking was under strong control and some ideas were violently repressed29On this particular matter, one can refer to: Robert I. Moore, 2012. The War on Heresy: Faith and Power in Medieval Europe, Profile Books, London., the work of François Rabelais (1483 or 1494 – 1553), for example, bears testimony of this. Nevertheless, we have seen that there are elements that call into question the presentation made by the encyclopedists concerning the evolution of ideas. On the subjects of science, which forms the particular topic of this article, liberty seemed greater than what is often claimed. To clarify, allow me to go back to the rediscovery of Aristotle in Europe.

An ambivalent domination

For Aristotle’s teaching had been partly forgotten in Europe. It was preserved mainly in Byzantium and then in the Muslim world. During the Renaissance of the twelfth century (a period of renewal of the cultural world in the Europe of the Middle Ages), the School of Chartres will rediscover the Greek philosopher30See for instance: Etienne Gilson, 1990. The Spirit of Medieval Philosophy (Gifford Lectures 1933-35), University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana, United States of America., then Albrecht von Bollstädt, also known as Albert the Great, (circa 1200 – 1280) translated his writings from Greek to Latin and commented on them, among other works. Thomas Aquinas (1224 or 1225 – 1274) will rely on this work to build his own. Scholasticism–in which Aristotle’s philosophical system, with some modifications, is an essential basis–is then clearly established, even if it will undergo evolutions over time. It will then spread in universities and academies.

From then on, scholasticism will be the main thinking system of Christendom. Because of its central position in this philosophy, the Aristotelian system is therefore the dominant system of the time.

However, there were some ambivalence in this domination. Thus, during his lifetime, Thomas Aquinas was at the heart of academic quarrels, especially against the Mendicant orders such as the Franciscans, and also against some masters of the arts (that is to say, teachers)31See for instance: Eleonore Stump, 2003. Aquinas, Routledege, Abington-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom.. Moreover, as early as 1270 and 1277, Étienne Tempier (1210 – 1279), then bishop of Paris, condemned 219 propositions, among which about fifteen were part of the Aristotelian thought32Stephani Tempier, 1270 then 1277. Codempnationes, Paris. Text in Latin. Available on-line.–however, this condemnation was more about the formulations of Averroes (1126 – 1198) than on those of Thomas Aquinas. Other condemnations will occur, but also defences, Thomas Aquinas being canonized in 1323 by Pope John XXII (Jacques Duèze also known as John XXII, 1244 – 1334).

Thus, throughout the second half of the Middle Ages, though the Aristotelian system is dominant, it is questioned, criticised, amended, and modified. Anyway, the authors of these criticisms were not worried by the religious authorities. Therefore, it was far from a system whose questioning was prohibited.

However, the vision of the Enlightenment was not entirely erroneous. Especially since a major turning point in Christian thought will change everything: Reformation.

Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation

I guess you are starting to understand that the change of philosophical system, in this case rather the emancipation of science from philosophy, is more the result of a long maturation than a sudden change in some people’s way of thinking. As a result, I think you will be quite easily convinced that, likewise, the appearance of Protestantism is the result of a somewhat long term evolution. Therefore, summarising it briefly is a challenge, which I must try to address anyway–and, to my sorrow, probably not entirely achieve33For a more complete presentation of the different currents that led to the Protestant Reformation, one can consult: Euan Cameron, 2012. The European Reformation, second edition, Oxford University Press..

Questioning the practices of the Church

Though the use of mobile printing characters, facilitating the distribution of books and therefore their access, played an important role, the event that can be considered to catalysed in 1517 the formation of the movement of Reformation is the publication by Martin Luther (1483 – 1546), placarding it on the front of his church, of a text often referred to as the Ninety-five Theses34Martinus Luther, 1517. Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum, Wittemberg, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. Available on-line. An English version can be found in: Timothy J. Wengert, 2015. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses: With Introduction, Commentary, and Study guide, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America. Available on-line..

Again, this publication is the result of a long term process, but it is the moment when it becomes truly apparent. It will highlight questions about the practices of the Church. Martin Luther first attacked indulgences, that is to say the practice of buying forgiveness by means of more or less generous donations to the Church. However, the questioning ultimately concerned a large part of the practices of the Catholic Church.

I guess it is quite well-known that at the time Catholic church was an essential political and financial power in Europe, as well as the moral and religious reference35On this subject, one can consult for instance: R. Po-chia Hsia (editor), 2008. “Reform and Expansion 1500–1660,” volume six of The Cambridge History of Christianity, Cambridge University Press.. However, the spreading of printing work lead a growing number to question whether such a power was both legitimate and consistent with the words of Jesus. Indeed, he is supposed to have expelled merchants from the Temple36Matthew 21:12-17, Mark 11:15-19, Luke 19:45-48, and John 2:13-16. and his magisterial is presented as purely spiritual rather than secular.

Therefore, the Protestant Reformation movement intended to return to practices closer with the origin of Christianity. However, one should notice that at the time, actually even now, it was difficult to really evaluate what the practices of the first Christians were. Especially, they gathered in communities with various practices, not to say opposite37On this subject, one can consult: Margaret M. Mitchell and Frances M. Young (editors), 2006. “Origins to Constantine,” volume one of The Cambridge History of Christianity, Cambridge University Press.. In fact, the Protestant Reformation is truly part of the questioning of its time, in relation to what was cultural life then.

At least in the period of its appearance, it seems that Protestant movements were opposed to the Copernican system (the starting point of this article). Thus, if Martin Luther did not express himself very much on the subject, there is a very clear condemnation of the Heliocentric system in his Table Talk38Martin Luther, 1566. Tischreden, edited by Johannes Mathesus, J. Aurifaber, V. Dietrich, Ernst Kroker, et al., Eisleben, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. A translation in English by William Hazlitt: Martin Luther, 2005. The Table Talk of Martin Luther, Dover Publications Inc, Mineola, New York. Available on-line. I am referring to entry 4638.. It also seems that John Calvin (1509 – 1564), another founder of a Protestant movement, was opposed to it39If you know some French, you can consult: Richard Stauffer, 1971. “Calvin et Copernic,” Revue de l’histoire des religions, 179 (1), pp. 31 – 40. Text in French. Available on-line..

The reaction of the Church

Still, a reformation desire, at first from within, was growing. This will was confronted to an opposition that won several victories, while the reformation movement became more radical. Thus, Martin Luther will be excommunicated in 1521 by Pope Leo X (Giovanni di Lorenzo de Medici also known as Leo X, 1474 – 1521)40Leo X, 1521. Decet Romanum Pontificem, Vatican. Text in Latin. Available on-line via Wikimedia. An English translation is available on-line., as he showed an increasingly firm opposition to the papal power.

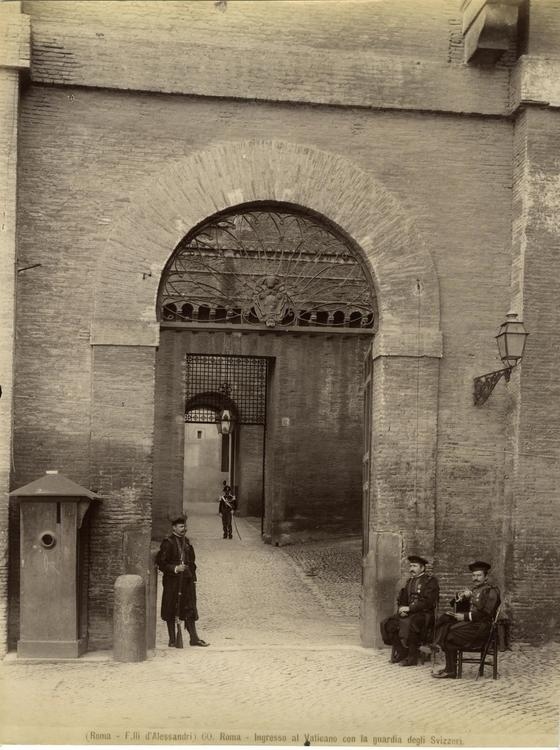

This will not end these oppositions and, as Martin Luther wanted, Pope Paul III (Alessandro Farnese also known as Paul III, 1468 – 1549) will convene in 1542 a council in the Italian city of Trento41For details on this council, one can refer to: John W. O’Malley, 2013. Trent: What Happened at the Council, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America.. This council began in 1545 and lasted 18 years, ending in 1563. If at the time some still had some hope of reforming from the interior, this hope was deceived. Instead, the Council of Trent was rather the occasion to organised what will be called later the Counter-Reformation, which opposes Protestantism.

Taking back control of universities

To stop the contamination by the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church will try to strongly take over the teaching of universities–according to the wordings of the time, the faculties of the arts, as opposed to the faculty of theology–considered to be too much independent. After all, this reform was the product of the questioning of the teachings of the Church. A list of books whose reading is forbidden to Christians, the Index librorum prohibitorum42Romæ Inquisitionis, 1559. Index Auctorum et librorum prohibitorum, Romæ ex officina. Text in Latin. Available on-line. (often simply referred to as the “Index”), has been created. Looking closely at it, what reaffirmed Counter-Reformation is the authority of the Church.

This desire to strengthen the Pope’s authority arise almost as early as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. For instance, several of Aristotle’s positions concerning the mortality of soul will be condemned by Leo X as soon as 151343Leo X, 1513. Apostolici Regiminis, papal bull, Vatican. Text en Latin..

However, to return to the ambivalence concerning Aristotle’s thought, let us note that the Council of Trent will reaffirm that transubstantiation during Eucharist is part of dogma. Transubstantiation was formalised by Thomas Aquinas based on Aristotle’s metaphysics44If you know some French, you can consult: Yves Gingras, 2010. “L’Atomisme contre la transsubstantiation,” La Recherche n° 446, pp. 92 – 94.. According to Aristotle, matter is composed of first qualities (the substance itself) and second qualities (sensations). According to transubstantiation, first qualities of the sacramental bread and wine are actually converted into the body and blood of Christ, while second qualities, that is to say both taste and consistency, are not changed.

This particular element of dogma became a point of opposition between the Catholic Church and the Reformed churches. Above all, note that despite a partial condemnation, the Aristotelian system is used to reaffirm Catholic dogma.

It seems that Vatican meddled with scientific subjects in reaction with the Protestant Reformation. In facts, instigators of Protestant Reformation and those of Counter-Reformation mutually provoked a hardening of positions on the other side.

At this point, Copernicus’ writings were not brought to the Index: after all, what was important for papacy at this time was to fight against Protestantism. It is Galileo’s work, more than half a century later, that lead the congregation of the Index to take some new interest in Copernicus’ publications45Concerning the ins and outs of Galileo affair, one can refer to: Emerson Thomas McMullen, 2003. “Galileo’s condemnation: the real and complex story,” in Georgia Journal of Science, volume 61, number 2, pp. 90 – 106..

Galileo affair

Indeed, Dominican brother Tommaso Caccini (1574 – 1648) delivered a sermon against mathematicians in December 1614, denouncing in particular Galileo’s support for Copernican theory. In response, Galileo’s supporters spread a letter from Galileo written a year earlier defending the position of accommodation (which I have mentioned earlier): it asserts that the Bible is compatible with the heliocentric model and, as cosmology does not concern the salvation of souls, in this field science is independent of theology. As a consequence, biblical studies have to adapt their interpretations to the findings of scholars.

Some fragile compromise

Thus, not only does Galileo meddle with theology, he also asserted that on some subject the Church cannot be considered as the authority. If you have followed me, you should realise that this position is contrary to the tendency initiated with the Council of Trent. Then, for ecclesiastic authorities, it was important to put Galileo back to his place. Thus, Caccini denounced Galileo to the Inquisition on March 20th, 1615.

Clearly, this first denunciation was not made on scientific basis, but for political reasons.

At first, Galileo submitted and a compromise had been set up in 1616: Galileo will not be condemned, while Copernicus’ writings in their original version will be put on the Index. However, as they were useful for astronomical computation, a version modified accordingly to Ossiander’s warning will be authorised, which state this system as nothing but a computational hypothesis. Therefore, it is presented as allowing more precise calculations than Ptolemy’s, but not reflecting reality. This act of submission reaffirmed the primacy of theologian.

Around 1624, Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini also known as Urban VIII, 1568 – 1644) enjoined Galileo to produce a book presenting equitably geocentric and heliocentric systems. The result, the Dialogue on the two chief world systems, was published in 163246Galileo Galilei, 1632. Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo, Batista Landini, Florence. Text in Italian. Available on-line. An English translation by Stillman Drake: Galileo Galilei, 1953. Dialogue concerning the two chief world systems–Ptolemaic & Copernican, second edition, University of California Press. Available on-line.. By reading this book, Copernicus’ system clearly appears to be more rightful than Ptolemy’s. However, at the time Galileo’s political supports was either dead or in weakened. As a result, the compromise of 1616 will be considered violated, Galileo will be condemned in 1633 to abjure heliocentric system and his works, as well as those of Copernicus, including in their modified versions, will be added to the Index.

Was it an act of defiance?

Please allow me to open some parenthesis. It is sometimes said that Galileo had shown arrogance, even that he defied papal power. Admittedly, it seems that Galileo had an important ego and that he tried to press his advantage when publishing the Dialogue on the two chief world systems, among other blunders. However, it is hardly conceivable that he knowingly took the risk of incurring the pope’s wrath.

Still, at that time he had gathered enough evidences to conclude that Ptolemy’s system was invalid. As a result, a balanced presentation could not present the two systems as equally likely, it would have been favouritism towards Ptolemy. But obviously the Church, while trying to reaffirm its authority, will present as some arrogance to affirm a position it disapproves. For instance, this is what it told previously about Giordano Bruno (1548 – 1600), which, as I have already stated, was condemned for his theological positions rather than his cosmological views.

The consequences of Galileo’s condemnation

After Galileo’s trial, at first the Church seemed to triumph: once again the scientist had to submit, theological authority seemed to prevail. René Descartes (1596 – 1650) even renounced to publish his treatise entitled The World47See for instance: Desmond Clarke, 2006. Descartes: A Biography, Cambridge University Press., completed in 1633 and which was published posthumously48René Descartes, 1664. Traité du monde et de la lumière. Text in French. A bilingual (French and English) edition with a translation by Michael Sean Mahoney: René Descartes, 1979. Le Monde, ou Traité de la lumière, Abaris Book, New-York. Available on-line.. This treatise presents a physical theory favourable to the heliocentric system.

However, after being condemned, Galileo published a last book which clearly contradicted Aristotelian physics49Galileo Galilei, 1638. Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche Intorno a Due Nuove Scienze, Leyde, Holland. Text in Italian. Available on-line. An English translation by Stillman Drake: Galileo Galilei, 1974. Two New Sciences, University of Wisconsin Press. Available on-line.. Moreover, rejection of Aristotle’s physics will quite soon become the norm. Especially with Newton’s works, while with the Enlightenment the intellectual world will definitively get rid of scholastic. After this seemingly triumph, quite soon the Church will not be able to impose its views to scientists.

Copernicus’ and Galileo’s books were removed from the Index in 1757 and 183550If you know some French, you can refer to: Pierre-Noël Mayaud, 1997. La Condamnation des livres coperniciens et sa révocation à la lumière de documents inédits des Congrégations de l’Index et de l’Inquisition, Université pontificale grégorienne. Partially available on-line.. In 1981, Pope John Paul II (Karol Józef Wojtyła also known as John Paul II, 1920 – 2005) created a special commission to review 1633 condemnation51See for instance: Michael Segre, 1999. “Galileo: A ‘rehabilitation’ that has never taken place,” Endeavour, 23 (1), pp. 20–23. Doi: 10.1016/s0160-9327(99)01185-0.. In 1992, he asserted that this condemnation was a mistake, even declaring that Galileo had turned out to be a better theologian than theologians of the times.

Then, the Catholic Church will react slowly, but became more ambiguous in its desire to impose its views in scientific matters. This even by leaving some points unresolved. For example, it would prefer not to directly condemn Charles Darwin52Charles Darwin, 1859. On the Origins of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, John Murray, London. Available on-line. (1809 – 1882), but still put on the Index works from other authors who supported evolution: despite it was repugnant to the idea of evolution of the species, not to attack Darwin directly is a way to avoid creating a new case similar to Galileo’s53Once again, forgive my being French, but on this subject you can consult: Yves Gingras, 2016. L’impossible dialogue, PUF, Paris. Text in French.. Therefore, although reluctant to the idea of evolution, it abandoned the frontal opposition to Reformed churches. However, John Paul II still indicated in 1996 that evolution is more than a hypothesis.

I hope these developments have convinced you that, contrary to what authors of the Enlightenment have written, there has not been a sudden shift from obscurantism to reason, but a series of developments and contradictions. However, we must not blame them too much: even if their strong convictions has lead them to some mistakes, we must remember that historical science was not really developed in their time. They were nevertheless at the origin of many scientific and cultural progress. Simply, we should analyse their points of view in the light of our current knowledge.

Science is not only occidental

It seems to me important to remember that not all scientific developments are made in the Western world. For instance, as I stated earlier, the Arab world has preserved and perpetuated the ancient Greek heritage. Not only did it preserve the Greek sciences, but it also made them evolve, notably by criticizing the occult aspects, such as magic and astrology54See for instance: F. Jamil Ragep and Sally P. Ragep (editors), 1996. Tradition, Transmission, Transformation. Proceedings of two Conferences on Pre-modern Science held at the University of Oklahoma, E. J. Brill, Leiden, New-York, Köln.. In this aspect, this is the seed that leads to modern scientific methodologies.

Although it seems that Copernicus has never been in direct contact with the Middle East, it is more than likely that he became acquainted with Arab thinkers during his studies in Italy, notably at the University of Bologna. It is based on ancient texts that he developed a complete astronomical system, which cannot be summed up as just a heliocentric system55See for instance: Thomas Samuel Kuhn, 1957. The Copernican Revolution, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America..

Thus, not only did Middle East preserve Greek philosophy, it also prolonged it. On the few topics covered in this article, I have cited sources from Greek and Roman antiquity, India, the Arab world, and the Western world. A certain kind of ethnocentrism led some to believe that science is primarily a creation of the Western world. Interestingly, proponents of a rigorous Islam, for instance, join this idea and talk about a so called Western science56This is the last reference in French which is not translated in English I give, but on this touchy subject, the following book gives elements way better than I can do: Faouzia Charfi, 2013. La Science voilée, Odile Jacob, Paris. Text in French..

However, history of science and more generally history of ideas on the contrary show rather regular exchanges between the different cultural areas. For instance, mobile printing characters, that I have mentioned above and that led to a cultural growth, where invented in China. Such exchanges have existed since a long time: the wheel, already57Readers interested on history of wheel, as well as origins of Indo-European languages can refer to: David W. Anthony, 2007. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, United States of America. …

A more modern vision

More recently, during the twentieth century, recognising that these revolutions actually inherits from works that preceded them, epistemology and philosophy of science reconsidered the idea of scientific revolution. For instance, according to Gaston Bachelard (1884 – 1962), strongly influenced by psychoanalysis, history of science is punctuated by a series of breaks58Gaston Bachelard, 1938. La Formation de l’esprit scientifique, Vrin, Paris. Text in French. Available on-line. An English translation by M. McAllester Jones: Gaston Bachelard, 2002. The Formation of the Scientific Mind, Clinamen, Bolton, Grand Manchester, United Kingdom.. These breaks make it possible to go beyond what he called “epistemological obstacles,” that is to say when the old theories fail to explain an observed phenomenon. Scientific revolutions would therefore be the engine of progress for humanity.

In contrast, for Thomas Samuel Kuhn (1922 – 1996)59Thomas Samuel Kuhn, 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, University of Chicago Press., a scientific revolution is not the remodelling of the concepts and axioms in use. According to him, scientific revolutions must also be considered as a social phenomenon. For him, usual practices of science consist in using and specifying the paradigms in use. He thus introduces in epistemology the notion of paradigm, designating a set of proven observations and an explanatory system of this set of observations, as well as a methodology for their study. Then, a scientific revolution would be a moment of crisis, when one or more paradigms are challenged.

However, Thomas Kuhn’s positions tend strongly to relativism. Also, history of natural sciences, for instance, shows that several competing paradigms can coexist at the same time and over a relatively long period, without one taking over the others. This led to question these positions.

Is it relevant to talk about revolution?

There is indeed in history of science several controversies, that is to say moments when some theories compete each other. In such cases, proponents of each theory give both arguments in favour of their point of view and against the opposing points of view. The evaluation of these arguments and the systematic search for errors lead then to invalidate certain theories–even, sometimes, all theories in competition.

Also, there are many moments of rupture, when certain elements of the scientific consensus are questioned, new fields are explored or new methodologies are set. However, the study of these ruptures shows that they are generally the result of a maturation of pre-existing ideas and questions.

The fragilities of the concept

But it seems to me that the idea of scientific revolution is based on an aristocratic vision of science, which would progress through several breakthroughs made by few individuals who would see further than the others. As I have already stated, not only does this point of view seem to me wrong, but also problematic.

Firstly, wrong because it does not fit with the practices I have seen in my personal experience: scientific work is a collective work, that even cannot really be made in isolation. Indeed, the first step in such a work is to be mistaken, then collectively look for errors. Also, it is through a collective work that a given contribution can be made objective–understood in the sense “which resist to the change of point of view.”

Secondly, problematic because the idea that contributions of a few would be intrinsically superior to any others leads to have too much deference for them. However, scientific practice consists not so much in doubt, but rather in systematic search for errors. To treat with too much deference a given contribution on the basis that the understanding of those who produced it is deemed to be superior to that of any other can lead to no longer carry out this search for errors. Therefore, it would prevent to advance, even to rely on invalid elements.

Moreover, to consider nothing but moments of emergence of possible controversies or ruptures leads to forget that questioning are permanent in the practice of science. Actually, this is central in science: systematic search for errors can only be made through constant questioning. If, indeed, this permanent questioning leads proportionally only rarely to controversies or ruptures, it is precisely because validity of theories is constantly questioned. This is what strongly establish them.

Finally, wrong again because, as we have seen with the examples discussed throughout this article–there are several others, some of them will be discussed later in this blog–, what is presented to be a rupture with previous point of view is often the result of a long process made by several contributors. Thus, considering only the scientific side, the idea of revolution is problematic.

The example of Galileo is thus significant: if it had been only a question of science, it appears quite clearly that acceptance would not have been a problem. He had indeed convinced the scientific community of his time. However, his work collided with a tense political context in which the Catholic Church was trying to strengthen its power.

What do I think about it?

My point of view is that a scientific revolution is not a purely scientific event. In fact, this term refers to a moment when scientific evolutions are connected with the questions of societies of the time. Scientists themselves are not hermetic to the society in which they live, so it certainly influences the topics they are addressing. However, in the case of what is described as a “scientific revolution,” it is rather a case where scientific advances are influencing society.

Since this is a practical name, I would still use this term in this blog. However, let it make clearly understood that it is ultimately a matter of naming those moments when scientific advances meet the questioning of the time.

Then, what about me?

In this blog, I indicated that the Aristotelian system can be made compatible with the Bible. Though I do not reject this way to put things, ever since I wrote it I had the objective to discuss it: in this previous article, my main goal was to highlight how much this system was compatible with medieval thought. Thus, I avoided to focus on the real but ultimately few–especially given the size of the corpus–problematic topics. However, I wanted to come back on it, because this formulation can lead to a misconception about the historical status of the Aristotelian system. Starting with the idea that it was considered complete and that it was forbidden to question it. Also, that this status has not changed over time.

My own limits

Alright, I have never been entirely satisfied with this wording, but I used it for lack of anything better considering my point then. Therefore, I had the firm intention to come back on it, which is one of the purposes of this article. I wanted to come back on the term “scientific revolution” as well.

The primary purpose of this series of articles is to present my research topics. I think a historical approach ease the understanding. I also think this approach make it easier for me to show how the scientific work is done, which also seems to me an important element to present.

However, I am facing two possible pitfalls.

Firstly, I cannot give all the ramifications of a given subject, or it will overflow my point. This article is an example: I have no prevention concerning the length of the articles, nor to go in deep of a subject. However, one cannot use up these topics, therefore I am forced not to address every element.

For instance, I did not give details about the relationship between Galileo and Kepler, which had not always been cordial, to say the least60On this subject, one can consult: Massimo Buccianti, 2003. Galileo e Keplero : Filosofia, cosmologia e teologia nell’Età della Controriforma, Biblioteca di Cultura Storica. Text in Italian.. Also, I did not indicate that Kepler was an astrologer and that him too tried to determine the age of the Earth using the Bible. These last two points may seem surprising considered with nowadays point of view, but we must not forget that the scientific method was then in its infancy, Kepler having contributed to establish it.

Therefore, I try to find the right balance between giving enough detail to avoid giving an erroneous view of events and avoiding overflowing my point with too many elements. By the way, if you have read a bit of these web-pages, you may have noticed I made evolve the balance in my articles to favor a little more precision rather than brevity, in particular to avoid using formulations on which I would like to come back–by the way, do not hesitate to tell me in the comments what you think of this balance.

The second pitfall comes from the fact that I set myself a double objective. On the one hand, I try to present my domains according to the current state of the art. In this context, I use the historical approach to introduce step by step the various necessary notions, in accordance with current knowledge and vocabulary. On the other hand, I try to present the history that led to the establishment of this knowledge, beyond the clichés that may have setted up over time.

The risk is then anachronism, that is to attribute to some previous times ideas and point of view of more recent epochs. I try to indicate regularly the differences in naming and ways of thinking between the periods I mention in my articles and our times. However, I rather warn the reader about this problem.

Finally, there is one last risk: I am of course always liable to make a mistake. As you can easily see, I give numerous bibliographical references and links in my articles. The purpose is not to impress, but to fulfil three goals. First, to give leads for who would be interested in exploring further the topic. Second, to indicate from where I hold the information that I transmit and what justifies my intention. Finally, just as importantly, these references should make it easier for every reader to look for my errors, so that you can tell me if there are erroneous elements in my articles–if you find any, please report them to me and I would be more than happy to correct them.

There is still much to be said

Concerning this particular article, I hope it will lead to some thinking, as well as some criticism concerning my writings. I also hope you will keep such a state of mind while consulting this series of articles. By the way, the next one would probably focus on mathematics.

There are still so many things I want to present to you, so my conclusion is that I hope you will come back here soon!

Notes

| ↑1 | Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖος, around 150 AD. Μαθηματική σύνταξις. An English translation: Gerald J. Toomer, 1998. Ptolemy’s Almagest, second edition, Princeton University Press, New York, United States of America. Available on-line. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert (editors), 1751-1772. Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Briasson, David, Le Breton and Durand, Paris, 35 volumes. Text in French. Available on-line. An English translation of some of its articles is available on-line. |

| ↑3 | Especially his most famous one: Isaac Newton, 1687. Philosophiæ naturalis principia mathematica, John Streater, London. Text in Latin. Available on-line. An English translation: Ierome Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman, 1999. Isaac Newton: The Principia, Mathematical principles of natural philosophy, University of California Press. Available on-line. |

| ↑4 | Immanuel Kant, 1781. Critik der reinen Vernunft, Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, Riga, Holy Roman Empire. Text in German. Available on-line. An English translation from Paul Guyer and Allen Wood: Immanuel Kant, 1999. Critique of Pure Reason, Cambridge University Press. Available on-line. |

| ↑5 | Áρχιμήδης, Ψαµµίτης. Text in ancient Greek. Available on-line. An English translation by Thomas L. Heath: Archimedes, 1897. The Sand-reckoner, Cambridge University Press. Available on-line. |

| ↑6 | See for instance: Bertrand Russel, 1945. A History of Western Philosophy, Georg Allen & Unwin Ltd. |

| ↑7 | See for instance: Abu al-Rayhan Muammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni, edited by Eduard Sachau, 1910. Al-Biruni’s India: an Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of Indiae, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., London. |

| ↑8 | Nicole Oresme, 1377. Livre du Ciel et du Monde. Text in ancient French. Available on-line. |

| ↑9 | See for instance: Victor Robert and Edward S. Kennedy, 1959. “The planetary Theory of Ibn al-Shātir,” in: Isis 50, pp. 227 – 235. Available on-line. |

| ↑10 | Nicolaus Copernicus, 1543. De revolutionibus orbium cœlestium, Johann Petreium, Nuremberg, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. Available on-line. An English translation by Edward Rosen: Nicolaus Copernicus, 1992. On the Revolutions, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America. Available on-line. |

| ↑11 | See for instance: John Henry, 2012. A Short history of scientific thought, Palgarve Macmillan, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom. |

| ↑12 | Nicolaus Copernicus, between 1511 and 1513. De Hypothesibus Motuum Cœlestium Commentariolus. Text in Latin. An English translation can be found in: Edward Rosen, 2004. Three Copernican Treatises, second edition, revised edition, Dover Publications, New York. Available on-line. |

| ↑13 | Georg Joachim von Lauchen, 1540. Narratio prima, Franz Rhode, Dantzig, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. An English translation can be found in Rosen (2004), see note 12. |

| ↑14 | For Copernicus’ biography, one can refer to: Pierre Gassendi and Olivier Thill, 2002. The Life of Corpernicus 1473 – 1543, Xulon Press. |

| ↑15 | Erasmo Reinholdo, 1551. Prutenicæ Tabulæ Cœlestium Motuum, Ulrich Morhard, Tübingen, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. Available on-line. |

| ↑16 | Johannes Kepler, Nicolaus Copernicus, Michael Mästlin, and Johannes Shöner, 1596. Mysterium cosmographicum, Georgius Gruppenbachius, Tübingen, Holy Roman Empire. Reissued in 1621 with comments from Kepler. Text in Latin. Available on-line. |

| ↑17 | Galileus Galileus, 1610. Sidereus nuncius, Thomam Baglionum, Venice. Text in Latin. Available on-line. An English translation: Albert Van Helden, 1989. Galileo Galilei, Siderius Nuncius, or The Sideral Messanger, The University of Chicago press. Available on-line. |

| ↑18 | Ivano Dal Prete, 2014. “Being the World Eternal: The Age of the Earth in Renaissance Italy”, in: Isis volume 105, number 2, pp. 292 – 317. |

| ↑19 | Fausto da Longiano, 1542. Meteorologia, Venice. Text in old Italian. |

| ↑20 | It seems to me that the seminal work concerning the importance of printing on the evolution of thought is: Elizabeth Eisenstein, 1979. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications and cultural transformations in early-modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, New York. The author has made a version dedicated to popularisation: Elizabeth Eisenstein, 1983. The Printing revolution in early modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. |

| ↑21 | James Ussher, 1650. The Annals of the World, E. Tyler, London. Available on-line. |

| ↑22 | See for instance: US Geological Survey, 1997. Age of the Earth. Available on-line. |

| ↑23 | Nicolau Aymerich, 1376. Directorium Inquisitorium. Text in Latin. This book has been completed (its size did more than doubled) by Francisco Peña in 1578. |

| ↑24 | Galileo’s letters exposing this point of view have been published and translated into English for instance in: Maurice A. Finnochiaro, 1989. The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History, University of California Press, Berkley. Available on-line. |

| ↑25 | See for instance: Raymond Edward Brown, 1997. An Introduction to the New Testament, Doubleday, New York City. |

| ↑26 | Aurelius Augustinus, 413-426. De Civitate Dei contra paganos. Available on-line. An English translation by William Babcock: Augustine of Hippo, 2012. The City of God, New City Press, New York. Available on-line. |

| ↑27 | Matthew 19:29, Mark 10:30. |

| ↑28 | Psalm 105:8. |

| ↑29 | On this particular matter, one can refer to: Robert I. Moore, 2012. The War on Heresy: Faith and Power in Medieval Europe, Profile Books, London. |

| ↑30 | See for instance: Etienne Gilson, 1990. The Spirit of Medieval Philosophy (Gifford Lectures 1933-35), University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana, United States of America. |

| ↑31 | See for instance: Eleonore Stump, 2003. Aquinas, Routledege, Abington-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom. |

| ↑32 | Stephani Tempier, 1270 then 1277. Codempnationes, Paris. Text in Latin. Available on-line. |

| ↑33 | For a more complete presentation of the different currents that led to the Protestant Reformation, one can consult: Euan Cameron, 2012. The European Reformation, second edition, Oxford University Press. |

| ↑34 | Martinus Luther, 1517. Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum, Wittemberg, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. Available on-line. An English version can be found in: Timothy J. Wengert, 2015. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses: With Introduction, Commentary, and Study guide, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America. Available on-line. |

| ↑35 | On this subject, one can consult for instance: R. Po-chia Hsia (editor), 2008. “Reform and Expansion 1500–1660,” volume six of The Cambridge History of Christianity, Cambridge University Press. |

| ↑36 | Matthew 21:12-17, Mark 11:15-19, Luke 19:45-48, and John 2:13-16. |

| ↑37 | On this subject, one can consult: Margaret M. Mitchell and Frances M. Young (editors), 2006. “Origins to Constantine,” volume one of The Cambridge History of Christianity, Cambridge University Press. |

| ↑38 | Martin Luther, 1566. Tischreden, edited by Johannes Mathesus, J. Aurifaber, V. Dietrich, Ernst Kroker, et al., Eisleben, Holy Roman Empire. Text in Latin. A translation in English by William Hazlitt: Martin Luther, 2005. The Table Talk of Martin Luther, Dover Publications Inc, Mineola, New York. Available on-line. I am referring to entry 4638. |

| ↑39 | If you know some French, you can consult: Richard Stauffer, 1971. “Calvin et Copernic,” Revue de l’histoire des religions, 179 (1), pp. 31 – 40. Text in French. Available on-line. |

| ↑40 | Leo X, 1521. Decet Romanum Pontificem, Vatican. Text in Latin. Available on-line via Wikimedia. An English translation is available on-line. |

| ↑41 | For details on this council, one can refer to: John W. O’Malley, 2013. Trent: What Happened at the Council, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America. |

| ↑42 | Romæ Inquisitionis, 1559. Index Auctorum et librorum prohibitorum, Romæ ex officina. Text in Latin. Available on-line. |

| ↑43 | Leo X, 1513. Apostolici Regiminis, papal bull, Vatican. Text en Latin. |

| ↑44 | If you know some French, you can consult: Yves Gingras, 2010. “L’Atomisme contre la transsubstantiation,” La Recherche n° 446, pp. 92 – 94. |

| ↑45 | Concerning the ins and outs of Galileo affair, one can refer to: Emerson Thomas McMullen, 2003. “Galileo’s condemnation: the real and complex story,” in Georgia Journal of Science, volume 61, number 2, pp. 90 – 106. |

| ↑46 | Galileo Galilei, 1632. Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo, Batista Landini, Florence. Text in Italian. Available on-line. An English translation by Stillman Drake: Galileo Galilei, 1953. Dialogue concerning the two chief world systems–Ptolemaic & Copernican, second edition, University of California Press. Available on-line. |

| ↑47 | See for instance: Desmond Clarke, 2006. Descartes: A Biography, Cambridge University Press. |

| ↑48 | René Descartes, 1664. Traité du monde et de la lumière. Text in French. A bilingual (French and English) edition with a translation by Michael Sean Mahoney: René Descartes, 1979. Le Monde, ou Traité de la lumière, Abaris Book, New-York. Available on-line. |

| ↑49 | Galileo Galilei, 1638. Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche Intorno a Due Nuove Scienze, Leyde, Holland. Text in Italian. Available on-line. An English translation by Stillman Drake: Galileo Galilei, 1974. Two New Sciences, University of Wisconsin Press. Available on-line. |

| ↑50 | If you know some French, you can refer to: Pierre-Noël Mayaud, 1997. La Condamnation des livres coperniciens et sa révocation à la lumière de documents inédits des Congrégations de l’Index et de l’Inquisition, Université pontificale grégorienne. Partially available on-line. |

| ↑51 | See for instance: Michael Segre, 1999. “Galileo: A ‘rehabilitation’ that has never taken place,” Endeavour, 23 (1), pp. 20–23. Doi: 10.1016/s0160-9327(99)01185-0. |

| ↑52 | Charles Darwin, 1859. On the Origins of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, John Murray, London. Available on-line. |

| ↑53 | Once again, forgive my being French, but on this subject you can consult: Yves Gingras, 2016. L’impossible dialogue, PUF, Paris. Text in French. |

| ↑54 | See for instance: F. Jamil Ragep and Sally P. Ragep (editors), 1996. Tradition, Transmission, Transformation. Proceedings of two Conferences on Pre-modern Science held at the University of Oklahoma, E. J. Brill, Leiden, New-York, Köln. |

| ↑55 | See for instance: Thomas Samuel Kuhn, 1957. The Copernican Revolution, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America. |

| ↑56 | This is the last reference in French which is not translated in English I give, but on this touchy subject, the following book gives elements way better than I can do: Faouzia Charfi, 2013. La Science voilée, Odile Jacob, Paris. Text in French. |

| ↑57 | Readers interested on history of wheel, as well as origins of Indo-European languages can refer to: David W. Anthony, 2007. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, United States of America. |

| ↑58 | Gaston Bachelard, 1938. La Formation de l’esprit scientifique, Vrin, Paris. Text in French. Available on-line. An English translation by M. McAllester Jones: Gaston Bachelard, 2002. The Formation of the Scientific Mind, Clinamen, Bolton, Grand Manchester, United Kingdom. |

| ↑59 | Thomas Samuel Kuhn, 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, University of Chicago Press. |

| ↑60 | On this subject, one can consult: Massimo Buccianti, 2003. Galileo e Keplero : Filosofia, cosmologia e teologia nell’Età della Controriforma, Biblioteca di Cultura Storica. Text in Italian. |