In this blog and elsewhere, you have probably already seen the expression “Copernican revolution”. This expression highlights the fact that Nicolaus Copernicus (1473 – 1543) provoked a major change in perspectives by showing that it is more relevant to consider this is the Earth that is rotating around the Sun rather than the opposite. To this first upheaval echoes Galileo Galilei’s (1564 – 1642) works. The latter, on the basis of Copernicus’ work, among others, has definitively shown that Claudius Ptolemy’s (around 90 AD – about 168) system, published in the Almagest1Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖος, around 150 AD. Μαθηματική σύνταξις. An English translation: Gerald J. Toomer, 1998. Ptolemy’s Almagest, second edition, Princeton University Press, New York, United States of America. Available on-line. and according to which, in agreement with Aristotelian physics, the Earth was motionless in the centre of the World, was wrong.

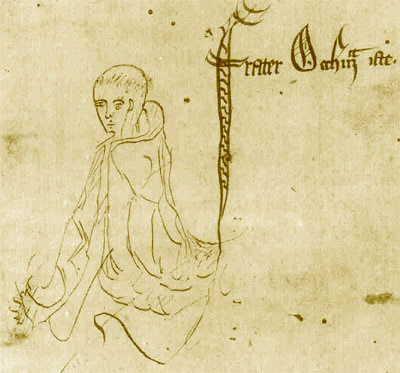

I have already presented this, with a view from here. As I have indicated before, they were both preceded by Nicole Oresme’s (about 1320 or 1322 – 1382) work. Galileo also used Johannes Kepler’s (1571 – 1630) work, among others. Therefore, I have intentionally used the expression “Copernican revolution,” as well as “epistemic revolution.” But still remains the question I would like to tackle in this article: though this expression is commonly used, is it really relevant to talk about revolution? My purpose is also to lead you, my dear reader, to make some critical analysis of what I am publishing here.

Continue reading Did Copernicus really made the (scientific) revolution?

Notes

| ↑1 | Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖος, around 150 AD. Μαθηματική σύνταξις. An English translation: Gerald J. Toomer, 1998. Ptolemy’s Almagest, second edition, Princeton University Press, New York, United States of America. Available on-line. |

|---|